Collecting Journals: Volume I, 1787-1808

The first volume in Lillian’s collecting journals opens by addressing the interesting question of defining American literature. Since she had decided that her collection would comprise bestselling American fiction, she had to make judgments on what constituted bestselling, what constituted American, and what constituted fiction. Her very first entry is for Charlotte Lennox’s The Female Quixote, but Lillian clarifies that this novel “is not to be put in the collection, but it is to go with the collection, and to be kept to the rear.” This is because Lennox does not qualify as an American according to Lillian’s guidelines: “Mrs. Lennox was born in New York, the daughter of Col. James Ramsay […]. At 15 she went to London. A brilliant woman, but not an American.” At the same time, Lillian realizes that she is making a judgment call, and acknowledges, “The future may class her as such.” Despite her assertion that The Female Quixote does not belong in her collection, she keeps it with the collection because she notes Lennox’s influence on later American novelists, including Tabitha Tenney. This question of what makes a particular work or author American (especially pertinent in the early national period) is one to which Lillian will return throughout this volume.

As she explores what defines bestselling American fiction, Lillian also takes care to record information about the provenance, textual variants, and rarity of the texts she gathers. She notes who else owns copies of her texts, how much she paid for them, where and how she obtained them, the character of the endpapers, dedications, gift inscriptions and non-authorial gift inscriptions, page numbering patterns, damaged pages, and more. As a part of this record keeping, Lillian carried on an extensive correspondence with bibliographer Lyle H. Wright, who published several bibliographies of American fiction. She also learned to repair books as part of her care for her collection.

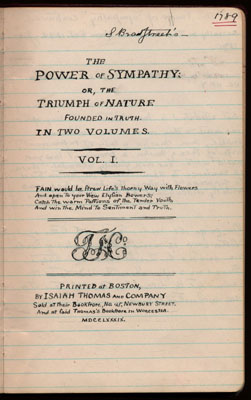

Along with her detailed attention to the physical object, Lillian takes a great deal of pleasure in exploring the history of her texts. For instance, in her entry on William Hill Brown’s The Power of Sympathy. Lillian writes, this is “The first novel written by an American and published in the U.S.A.” She records the early confusion about the novel’s authorship: “For years believed to have been written by Mrs. Sarah Wentworth Morton. Now the author is believed to be William Hill Brown[,] a neighbor of Mrs. Morton in Boston.” On a personal level, Lillian believes that Mrs. Morton is probably not the author: “Not attributed to Mrs. Morton until long after her death, and then on hear-say evidence. Unlikely Mrs. Morton[,] a lady of refinement, wife of Perez Morton, a prominent lawyer, would write her own family scandal. There is evidence to show she and Mr. Morton tried to suppress and destroy the book, which was widely discussed at its publication.” The important information that Lillian here elides is that the plot of the novel is based on a scandalous affair that is presumed to have taken place between Mr. Morton and his wife’s sister.

While Lillian enjoyed contemplating such historical backgrounds to her texts, she also treasured the texts themselves. She not only collected fiction, but she also loved to read it. In her entry for Jeremy Belnap’s The Foresters, she writes, “Bought in England, and it came to me, with many of the pages un-opened. I opened them so I could read it.” Some of her books she read repeatedly; and as Memories shows, her reading habits extended beyond American fiction to include writers such as Sir Walter Scott and Baroness Tautphoeus. She is also generous in her definition of fiction, including in her collection Samuel Lorenzo Knapp’s Letters of Shahcoolen. Lillian writes, “Mr. Wright omits this book from his Bibliography of Fiction, as too much like essays. A difficult line to draw. I include it.” This inclusion brings together her enjoyment in reading and in building a collection.

This combined love of reading and collecting fiction is clear in many of her entries. Her sheer excitement upon discovering a copy of Susanna Rowson’s Charlotte: A Tale of Truth (late to become Charlotte Temple) is infectious: “The first issue of the 1st American Edition!! Bought in Albany in June 1940 from John C. Scopes, for $150.00. I nearly fainted when I saw this among a dozen worthless old novels he brought for me to see.” Even as she becomes enthusiastic, she takes care to stay up-to-date on collecting logistics, writing, “[T]his page [of advertisements and criticism] is the sign of the first issue and is a recent decision—only known in 1939 that a difference exists in the M.DCC.XCIV. printings.” Despite her excitement, Lillian remains selective about American identity. For the second edition of Charlotte, she writes, “Will not pay big price for this an English woman’s novel. As it had about 100 Editions in America, and she lived here all but a few years of her life. I put in these early editions of hers, in spite of their having been written before she left England.” She later clarifies her position on Rowson in her entry on The Inquisitor: “Mrs. Rowson was English when she wrote this novel, and it was first published in London in 1788. It is only included with my American authors on account of the influence of Mrs. Rowson’s novels, and that she is generally classed with the Americans. I exclude those novels of hers published in England before her return to America. And this is English and a second edition, (America). Included for study, not for taste.” Trials of the Human Heart is the novel Lillian identifies as Rowson’s first American novel, as it was both written and first published in the United States. This is certainly an important distinction for Lillian, considering Rowson’s immense popularity in the States.