Cabells and the Founding of the University of Virginia

“If aught of good proceeds from the University, the pride and glory of Virginia, the member from Nelson cannot be forgotten; for he, in promoting that monument of wisdom and taste, was second only to the immortal Jefferson.”

Gen. Lawrence T. Dade of Orange Co., Va. in the General Assembly’s session of 1827-28

Joseph Carrington Cabell played such an important role in convincing the Virginia General Assembly to establish and succor the University of Virginia, and invested so much of his personal time and treasure in its welfare, that he may almost be considered its co-founder, alongside Thomas Jefferson. But Joseph C. Cabell was not the only member of his family, nor even the first, to champion that institution. As governor of the state from 1805-1808, his brother, William H. Cabell, had lent the prestige of his office behind the cause of higher education and of the University. In 1806, in his annual communication to the Assembly, W. H. Cabell had “most respectfully” called “the attention of the legislature, to the importance of schools for the most general diffusion of knowledge.” Undoubtedly, Cabell had in mind Jefferson’s “Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge,” formally introduced in 1779; at the heart of this mothballed proposal had been the establishment of a new state university to replace the sectarian College of William and Mary.

Joseph Carrington Cabell played such an important role in convincing the Virginia General Assembly to establish and succor the University of Virginia, and invested so much of his personal time and treasure in its welfare, that he may almost be considered its co-founder, alongside Thomas Jefferson. But Joseph C. Cabell was not the only member of his family, nor even the first, to champion that institution. As governor of the state from 1805-1808, his brother, William H. Cabell, had lent the prestige of his office behind the cause of higher education and of the University. In 1806, in his annual communication to the Assembly, W. H. Cabell had “most respectfully” called “the attention of the legislature, to the importance of schools for the most general diffusion of knowledge.” Undoubtedly, Cabell had in mind Jefferson’s “Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge,” formally introduced in 1779; at the heart of this mothballed proposal had been the establishment of a new state university to replace the sectarian College of William and Mary.

Not too many years after his retirement from public life, Jefferson again turned his attention to the establishment of a world-class institution of higher learning in Virginia. In 1814, he agreed to serve as a trustee of Albemarle Academy, a proposed secondary school of modest ambition in the Virginia piedmont. It was only a matter of months before Jefferson had captured the imagination of his fellow trustees and transformed the project into one of unprecedented scale. With or without the state’s help, Jefferson planned to build the “modern university’ of which he had long dreamed. Rather than a finishing school for locals, they would build an institution “where every branch of science, deemed useful at this day, should be taught in its highest degree.” Jefferson’s architectural vision was equally forward-looking; he wanted the school’s built environment to facilitate learning in and out of the classroom. Jefferson also wanted his university to succeed where his own alma mater, The College of William & Mary, had failed: to educate the sons of elite Virginians, spoiled by their dependence upon the institution of slavery, so that they might better perpetuate its democratic institutions and, ultimately, wean its citizens from their reliance on enslaved labor. His passions stirred, the “Sage of Monticello” turned to his friends for help, including the Cabells. Ironically, their vision would be realized only through the toil of hundreds of enslaved persons, some of whom they hired out for the purpose, who built the university’s structures and tended to the needs of its faculty and students during its initial four decades.

Joseph Carrington Cabell’s longevity only amplified his contributions to the founding of the University. Whereas Jefferson passed away on July 4, 1826, just over a year after the arrival of the first students, Cabell maintained an intimate involvement with the University through his death in 1856, serving as its Rector, or chairman of the Board of Visitors, from 1834-36 and again from 1845-56. He single-handedly provided the continuity so important to the nascent institution while helping to shape every aspect of its existence, from the curriculum to the support operations largely carried out by the enslaved persons owned or hired by the University and its faculty and staff. In personal ways, too, his presence shaped the direction the University took in its early days. Literally dozens of his kinsmen enrolled as students, and his precocious nephew, James L. Cabell began his career as one of the University’s most beloved instructors in 1837. The imprint of Joseph Carrington Cabell rests heavily indeed on Mr. Jefferson’s University.

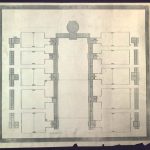

The Governor then named Jefferson, Cabell, their mutual friend John Hartwell Cocke, and four others to a Board of Visitors to superintend the construction of the University. J. C. Cabell did not rest from his labors after this official incorporation of the University, which was not to open its doors for another six years. He loyally stuck to his post in the Assembly and became adept at securing funds for the school, which Jefferson’s elaborate architectural designs and ambitions of international excellence continued to push deeper into debt. As a Visitor, J. C. Cabell collaborated with Jefferson to finalize the building plans, hire the first professors, and establish the course of instruction.

Joseph Carrington Cabell’s longevity only amplified his mammoth contributions to the founding of the University. Whereas Jefferson passed away on July 4, 1826, just over a year after the arrival of the first students, Cabell maintained an intimate involvement with the University through his death in 1856, serving as its Rector, or chairman of the Board of Visitors, from 1834-36 and again 1845-56. He single-handedly provided the continuity so important to the nascent institution, and–ever the loyal lieutenant–he was able to see the flowering of Jefferson’s vision. In personal ways, too, his presence shaped the direction the University took in its early days. Literally dozens of his kinsmen enrolled as students, and his precocious nephew, James L. Cabell became one of the University’s most beloved instructors in 1837. The imprint of Joseph Carrington Cabell rests heavily indeed on Mr. Jefferson’s University.

Additional Sources Consulted:

Philip Alexander Bruce, History of the University of Virginia (1921)

[Nathaniel F. Cabell], Early History of the University of Virginia (1856)

Educated in Tyranny: Slavery at Thomas Jefferson’s University (2019)

John S. Patton, Jefferson, Cabell, and the University of Virginia (1906)

Carol Tanner, “Joseph C. Cabell” (1948)

Alan Taylor, Thomas Jefferson’s Education (2019)