Gothic Gold: Appendix, Commentaries on the Engravings and Woodcuts

Originally published in Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture, vol.26, pp.287-[312], 1998.

© 1998 by The American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies

Reproduced here by permission of the author and The American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies

Images © 1998 by The Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia

Appendix, Commentaries on the Engravings and Woodcuts

The nine specimens of Gothic chapbook illustrating which follow are selective reproductions of covers and frontispieces facing the title pages of nine short Gothics in the Sadleir-Black collection and are arranged chronologically by author with unsigned Gothics following the signatured titles. The illustrations demonstrate publishers’ preferences for certain type scenes and horrid situations. Approximately one-third of the titles in Sadleir- Black are chapbooks, shilling shockers, and penny dreadfuls. The nine samples have been selected to give an overview of the typical chapbook cover and frontispiece of this primitive paperback industry. A statistical survey of the Sadleir-Black collection’s illustrated Gothics remains to be accomplished. Such a survey would also identify the number of titles in the collection that are unique or sole surviving copies, a category which embraces most of the chapbooks. Sadleir himself never attempted to determine what percentage of the novels in the collection were pure or high Gothics and which books were other shades of terror fiction. Except for the chapbooks which are all dependably horrid, the titles of the novels are not always an accurate guide to their Gothicity. In her bibliographical inventory of Sadleir-Black titles, Ann B. Tracy has noted that “Some quite promising titles led to disappointingly bland novels, while some rather neutral titles [e.g., Mary Jane by Richard Sickelmore] proved satisfyingly horrid.” 25

There are other collections of Gothic fiction elsewhere in the world, but none can rival the riches and wonders of Sadleir-Black. The Harvard, Yale, Illinois, and University of Toronto libraries have Gothic holdings. The Hammond collection of the New York Society Library, the Larpent collection of eighteenth-century plays in the Huntington Library, and a dispersion of American Gothic titles in the stacks of the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts present opportunities and resources for the Gothic researcher. The Prince Ludwig Starhemberg library of Gothics recently discovered by Devendra P. Varma at Schloss Eferding in Austria has profuse deposits of Gothic gold. But the supremacy of Sadleir-Black in this field will continue so long as these rare books are sought after and read. Writing of the Starhemberg discovery, Devendra P. Varma has commented that “the pages of Gothic fiction turn with a ghostly flutter.” 26 That same ghostly flutter remains eternally audible throughout the fascinating labyrinth of Sadleir-Black.

C. F. Barrett, The Round Tower: or, The Mysterious Witness, an Irish Legendary Tale of the Sixth Century (London: Tegg and Castleman, 1803), 36 pages. The chapbook frontispeice shows a tripartite figure arrangement depicting a Duncanesque deus ex machina, “his silver skin lac’d with his golden blood,” pronouncing lat judgement on the two Macbethian usurpers, Sitric and Cobthatch. As the murderers extend their left arms, the regal deity raises a righteous right arm in retribution. This is a Macbethian Gothic, a subtype of the shilling shocker designed to thrill the reader with gory supernatural spectacle.

C. F. Barrett, The Round Tower: or, The Mysterious Witness, an Irish Legendary Tale of the Sixth Century (London: Tegg and Castleman, 1803), 36 pages. The chapbook frontispeice shows a tripartite figure arrangement depicting a Duncanesque deus ex machina, “his silver skin lac’d with his golden blood,” pronouncing lat judgement on the two Macbethian usurpers, Sitric and Cobthatch. As the murderers extend their left arms, the regal deity raises a righteous right arm in retribution. This is a Macbethian Gothic, a subtype of the shilling shocker designed to thrill the reader with gory supernatural spectacle.

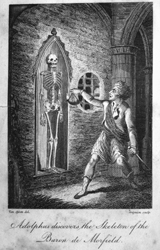

Isaac Crookenden, The Skeleton; or, The Mysterious Discovery, A Gothic Romance (London: A. Neil, 1805), 38 pages. A typical chapbook by the master counterfeiter of long Gothics, Isaac Crookenden. The illustration shows that mandatory moment of supernatural startle when the castle explorer comes face-to-face with the deceased or missing owner. Crookenden plundered the plot from The Animated Skeleton, a 1798 Minerva Press Gothic, and melted down its four hundred pages to the requisite thirty-eight page quota. If the baron’s bones are not quite animated here, neither are they immobilized as the illustrator has succeeded in giving an air of aliveness to the ossurial figure which seems about to descend from its niche.

Isaac Crookenden, The Skeleton; or, The Mysterious Discovery, A Gothic Romance (London: A. Neil, 1805), 38 pages. A typical chapbook by the master counterfeiter of long Gothics, Isaac Crookenden. The illustration shows that mandatory moment of supernatural startle when the castle explorer comes face-to-face with the deceased or missing owner. Crookenden plundered the plot from The Animated Skeleton, a 1798 Minerva Press Gothic, and melted down its four hundred pages to the requisite thirty-eight page quota. If the baron’s bones are not quite animated here, neither are they immobilized as the illustrator has succeeded in giving an air of aliveness to the ossurial figure which seems about to descend from its niche.

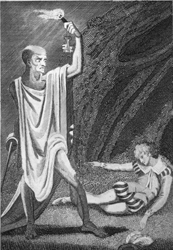

Lucy Watkins, Romano Castle; or, The Horrors of The Forest (London: Dean and Munday, n.d.), 35 pages. The signature of Lucy Watkins is to be found frequently among the chapbook authors. The chapbook also uses the device of the page direction which sends the reader without delay to the ghastly scene shown on the title page. Page 5 of Romano Castle reads: “As Alfonso advanced, he saw that the light was held by a gigantic being, a skeletal form with two flaming red eyes.” Brandishing the torch, keys, and cutlass, the skeletal apparition confronts and converts the rationalist who is seen in a stylized swoon as the figure nears.

Lucy Watkins, Romano Castle; or, The Horrors of The Forest (London: Dean and Munday, n.d.), 35 pages. The signature of Lucy Watkins is to be found frequently among the chapbook authors. The chapbook also uses the device of the page direction which sends the reader without delay to the ghastly scene shown on the title page. Page 5 of Romano Castle reads: “As Alfonso advanced, he saw that the light was held by a gigantic being, a skeletal form with two flaming red eyes.” Brandishing the torch, keys, and cutlass, the skeletal apparition confronts and converts the rationalist who is seen in a stylized swoon as the figure nears.

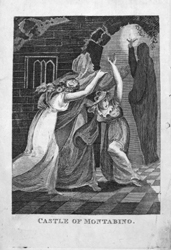

Sarah Wilkinson, The Castle of Montabino; or, The Orphan Sisters (London: Dean and Munday, 1810), 38 pages. A chapbook from the prolific pen of a leading lady chapbooker, Sarah Wilkinson, who haunted the chapbook marketplace for more than two decades and whose palette oozed every shade of blood. The single source of light in the engraving radiates from the phantom silhouetted in the Gothic archway. The moment is another stock Gothic scene, the spectral encounter when the thing from the other world confronts the maiden causing here a triple swoon of awestruck belief. Although the moral nature of the specter in the portal is indeterminate, the well-versed Gothic maiden, like The Mysteries of Udolpho’s Emily St. Aubert, when the black veil drops away from the portrait, will faint on cue during every liaison with the supernatural.

Sarah Wilkinson, The Castle of Montabino; or, The Orphan Sisters (London: Dean and Munday, 1810), 38 pages. A chapbook from the prolific pen of a leading lady chapbooker, Sarah Wilkinson, who haunted the chapbook marketplace for more than two decades and whose palette oozed every shade of blood. The single source of light in the engraving radiates from the phantom silhouetted in the Gothic archway. The moment is another stock Gothic scene, the spectral encounter when the thing from the other world confronts the maiden causing here a triple swoon of awestruck belief. Although the moral nature of the specter in the portal is indeterminate, the well-versed Gothic maiden, like The Mysteries of Udolpho’s Emily St. Aubert, when the black veil drops away from the portrait, will faint on cue during every liaison with the supernatural.

Sarah Wilkinson, Zittaw the Cruel; or The Woodsman’s Daughter, A Polish Romance (London: B. Mace, n.d.), 36 pages. Another curious corner of the Sadleir-Black Collection features Slavonic or Polish Gothic romances which seem to have enjoyed a steady vogue. Lengthy Slavonic Gothics such as Mary Charlton’s four-volume romance Phedora; or, The Forest of Minski (1798) and Thomas Pike Lathy’s The Invisible Enemy; or, The Mines of Wielitska, A Polish Legendary Romance (1806) published by Lane and Newman’s Minerva Press were widely read and went through successive editions. In chapbook form, Slavonic Gothics such as Zittaw the Cruel appealed strongly to the chapbook audience. The woodcut shows Zittaw in the uniform of a Russian hussar engaged in the arboreal seduction of the heroine, Amelia Perowitz.

Sarah Wilkinson, Zittaw the Cruel; or The Woodsman’s Daughter, A Polish Romance (London: B. Mace, n.d.), 36 pages. Another curious corner of the Sadleir-Black Collection features Slavonic or Polish Gothic romances which seem to have enjoyed a steady vogue. Lengthy Slavonic Gothics such as Mary Charlton’s four-volume romance Phedora; or, The Forest of Minski (1798) and Thomas Pike Lathy’s The Invisible Enemy; or, The Mines of Wielitska, A Polish Legendary Romance (1806) published by Lane and Newman’s Minerva Press were widely read and went through successive editions. In chapbook form, Slavonic Gothics such as Zittaw the Cruel appealed strongly to the chapbook audience. The woodcut shows Zittaw in the uniform of a Russian hussar engaged in the arboreal seduction of the heroine, Amelia Perowitz.

Idlefonzo and Alberoni; or, Tales of Horror (London: Tegg and Castleman, 1803). Argosies and anthologies such as Idlefonzo and Alberoni offered the Gothic reader sundry horrors based on medieval ballads and legends of the demon huntsman and ghostly rider. Shown here amidst “darkness visible” is the Gothic sampler’s frontispiece with the beckoning cadaverous figure inviting the human figures to take death’s last ride with him. The allegory of death’s victory over life has been captured by the illustrator’s rendition of death’s black stallion or the devil’s stud looking on appreciatively as the two mortals prepare to accompany their fiendish guide.

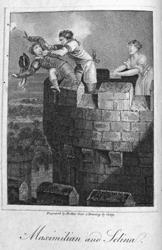

Maximillian and Selina; or, The Mysterious Abbot, A Flemish Tale (London: Tegg and Castleman, 1804), 36 pages. Sadleir-Black contains many short, unsigned Gothics manufactured and marketed by Tegg and Castleman. Fatal peril or deadly predicament atop a tower is a common dilemma for the Gothic victim. The perilous or infernal tower also figures prominently as a place for nefarious aspiration in Beckford’s Vathek . About to be hurled from the turret by his malicious brother, Adolphus de Monvel, Maximillian’s doom seems sealed as a pathetic mother figure murmurs an ineffectual prayer unheard in the fallen and godless universe. The scene is the chapbook’s initial spectacular incident in a series of unremitting crises.

Maximillian and Selina; or, The Mysterious Abbot, A Flemish Tale (London: Tegg and Castleman, 1804), 36 pages. Sadleir-Black contains many short, unsigned Gothics manufactured and marketed by Tegg and Castleman. Fatal peril or deadly predicament atop a tower is a common dilemma for the Gothic victim. The perilous or infernal tower also figures prominently as a place for nefarious aspiration in Beckford’s Vathek . About to be hurled from the turret by his malicious brother, Adolphus de Monvel, Maximillian’s doom seems sealed as a pathetic mother figure murmurs an ineffectual prayer unheard in the fallen and godless universe. The scene is the chapbook’s initial spectacular incident in a series of unremitting crises.

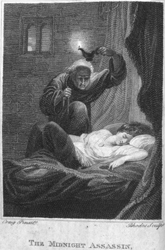

The Midnight Assassin; or, the Confessions of the Monk Rinaldi, containing a complete history of his diabolical machinations and unparalleled ferocity. Together with a circumstantial account of that scourge of mankind , the inquisition, with the manner of bringing to trial those unfortunate beings who are at its disposal. Marvellous Magazine and Compendium of Prodigies, May 1802. Serialized Gothics appearing singly or in installments in periodicals such as The Marvellous Magazine Compendium of Prodigies are yet another mutation of the Gothic novel. The Midnight Assassin is Mrs. Radcliffe’s The Italian reduced from three volumes to 30,000 words and heavily eroticized. The incubus poised at the maiden’s bedside is a creature of sexual nightmare complete with phallic dagger. The guardian locket on the maiden’s breast caused the Monk Renaldi to hesitate just as Father Schedoni had wavered over the sleeping figure of his niece, Ellena de Rosalba, in The Itallian’s climactic horror-and- recognition scene.

The Midnight Assassin; or, the Confessions of the Monk Rinaldi, containing a complete history of his diabolical machinations and unparalleled ferocity. Together with a circumstantial account of that scourge of mankind , the inquisition, with the manner of bringing to trial those unfortunate beings who are at its disposal. Marvellous Magazine and Compendium of Prodigies, May 1802. Serialized Gothics appearing singly or in installments in periodicals such as The Marvellous Magazine Compendium of Prodigies are yet another mutation of the Gothic novel. The Midnight Assassin is Mrs. Radcliffe’s The Italian reduced from three volumes to 30,000 words and heavily eroticized. The incubus poised at the maiden’s bedside is a creature of sexual nightmare complete with phallic dagger. The guardian locket on the maiden’s breast caused the Monk Renaldi to hesitate just as Father Schedoni had wavered over the sleeping figure of his niece, Ellena de Rosalba, in The Itallian’s climactic horror-and- recognition scene.

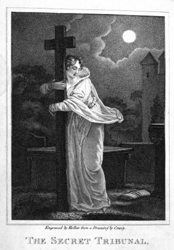

The Secret Tribunal; or, The Court of Wincelaus (London: Tegg and Castleman, 1803). A considerable number of novels in Sadleir-Black deal with the plots and counterplots of the Vehmgericht of secret Fehmic court, the Illuminati, Masonic societies, and other secret societies dedicated to international conspiracy and ritual sacrifice. The anonymous Secret Tribunal; or, The Court of Winecelaus (1803) is an utterly ordinary chapbook example of this Horrid Mysteries strain of Gothicism. The title page illustration, however, is an extraordinary projection of Gothic sublimity whose power overshadows the chapbook’s vapid text. All of the distorted religious iconography of the Gothic romance converges in this remarkable engraving. The melodramatic flight of the maiden through an eternal night and from some pursuing unseen force resonates with paradises lost forever. The castle or cathedral, once a refuge or sanctuary, now glowers on the horizon like Milton’s Pandemonium. The stark granite cross which the fleeing maiden embraces so desperately has ceased entirely to be a sacramental object and has become its very opposite, an emblem of ultimate terror. It is black, monstrous, and malignantly animated, its traditional salvational properties replaced by the graveyard gloom. Her hopeless flight has brought the maiden from one place of darkness and damnation to another equally dark and foreboding. Yet, she is determined to cling heroically to those decadent symbols of a religious and social order now morally transformed. The maiden in this illustration symbolizes the essence of the Gothic experience, that same “eloquent disequilibrium of the spirit” of which Sadleir had spoken in characterizing the Zeitgeist of Gothic romance.

The Secret Tribunal; or, The Court of Wincelaus (London: Tegg and Castleman, 1803). A considerable number of novels in Sadleir-Black deal with the plots and counterplots of the Vehmgericht of secret Fehmic court, the Illuminati, Masonic societies, and other secret societies dedicated to international conspiracy and ritual sacrifice. The anonymous Secret Tribunal; or, The Court of Winecelaus (1803) is an utterly ordinary chapbook example of this Horrid Mysteries strain of Gothicism. The title page illustration, however, is an extraordinary projection of Gothic sublimity whose power overshadows the chapbook’s vapid text. All of the distorted religious iconography of the Gothic romance converges in this remarkable engraving. The melodramatic flight of the maiden through an eternal night and from some pursuing unseen force resonates with paradises lost forever. The castle or cathedral, once a refuge or sanctuary, now glowers on the horizon like Milton’s Pandemonium. The stark granite cross which the fleeing maiden embraces so desperately has ceased entirely to be a sacramental object and has become its very opposite, an emblem of ultimate terror. It is black, monstrous, and malignantly animated, its traditional salvational properties replaced by the graveyard gloom. Her hopeless flight has brought the maiden from one place of darkness and damnation to another equally dark and foreboding. Yet, she is determined to cling heroically to those decadent symbols of a religious and social order now morally transformed. The maiden in this illustration symbolizes the essence of the Gothic experience, that same “eloquent disequilibrium of the spirit” of which Sadleir had spoken in characterizing the Zeitgeist of Gothic romance.