Collecting Journals: Volume XVII, 1941-1945

Lillian begins Volume XVII with a long quote from John Buchan (Lord Tweedsmuir) on the pleasures of reading, copied from his “Pilgrim’s Way: an Essay in Recollections.” The passage relates well to Lillian’s various reflections throughout her collecting journals about reading for pleasure and assessing literary merit. Buchan writes, “I believe that the taste in literature of most people sets in early in life, and in essentials does not alter except in the case of a few superior minds which remain always receptive and yet anchored to eternal values. […] A music lover who can appreciate the austerest merits may also have an irrational liking for ditties which have no artistic credentials. So in literature, oddments are carried over from youth and continue to please, not because of their intrinsic quality, but because they were first read or heard on happy occasions, and the memory of them recalls those blessed moments. It is a pure sentimentality, but how many of us are free from it?” The corpus of her collection and collecting journals make it easy to see why this quote spoke to Lillian.

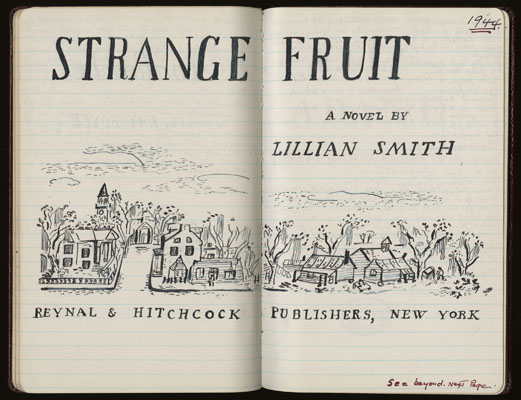

This volume, covering the years from 1941 to 1945, includes several interesting entries for banned books. Among these are Lillian Smith’s Strange Fruit, Joseph Stanley Pennell’s The History of Rome Hanks, and Kathleen Windsor’s Forever Amber. Of Strange Fruit, Lillian Taylor writes, “This book began life quietly. Then banned it sold. Then I bought my copy, guessing the result. […] Its indecency is being lost, in a fight for Civil Liberty. The Freedom of the press, etc. I will not read it, but it is selling fast. […] I have read enough to know its coarseness.” She quotes a review by Edward Weeks for the “Atlantic,” who says that Strange Fruit “discloses with a high voltage of emotion, themes which it is not polite to discuss—miscegenation, abortion, and white supremacy. To the leaders of both races such ideas are repugnant. Yet the book reached my heart.” In her entry for Forever Amber, Lillian includes this quote from the novel being banned in Australia: “The Almighty did not give people eyes to read that rubbish.” Of Charles Jackson’s The Lost Weekend, which was not banned and yet did not please Lillian, she writes, “I will enter one more book, and let the rest of the degenerate crew alone.”

Two other notes in the volume again reveal Lillian’s personal investment both in her journals and in literary circles. In the entry for Arthur Train’s The Yankee Lawyer: The Autobiography of Ephraim Tutt, Lillian states, “An affectionate letter from the author to me pasted on first end-paper. He a warm friend of ours for 43 years. In this letter he likens Bob to Mr. Tutt.” In Volume XIII, Lillian recounts how she and Bob guessed Train’s authorship of an anonymously published volume. In her note on Cass Timberlane, by Sinclair Lewis, Lillian regrets being unable to provide an exact replica of the title page: “I could not buy the proper blue ink, and at my age (80), life was too short to make that [intricate zigzag] border. I thought of buying an extra title page and pasting it in, but the color blue on the reprints is much paler than on the first editions. It is a pale green blue.” Even at 80, Lillian remains particular about the details of her collecting journals, preferring here to leave the border unfinished than to do a poor job of replicating it.