Collecting Journals: Volume II, 1834-1863

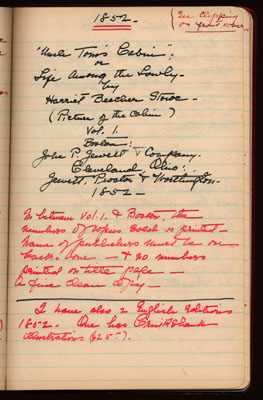

This volume appears to be a remnant from an earlier series of collecting journals: besides being labeled as a second volume two, it is poorly organized, difficult to read, and does not include hand copies of any title pages (though, like the newer volumes, it does include notes on the condition, price, place of purchase, etc. of the various works). The page to the right is a good illustration of these changes. Where Lillian has currently written (Picture of the cabin), she will later draw in the image. However, the volume is still quite interesting because not only because it represents an earlier stage in Lillian’s work in documenting her novels, but also because is offers a classification system unseen in her other collecting journals. Here Lillian takes care to differentiate between what she reads as books of literary merit and merely popular books:

“Books in violet box or entered in violet ink are books in their day very popular, or written by popular authors, devoid of literary merit. I have them in rows behind writers of established reputation. It is difficult to draw the line, and I would place many who are not in violet ink in that class. I can safely put Mary J. Holmes, E.D.E.N. Southworth, Augusta J. Evans, Marietta Holley, etc. in that category. Perhaps the future may reverse the present verdict (1-38).”

The books she places in violet ink include Linda, or the Young Pilot of the Belle Creole, by Caroline Lee Hentz, and Mrs. Harrison Gray Otis’s The Barclays of Boston. Perhaps the most interesting inclusion is Ruth Hall, by Fanny Fern (Sarah Payson Willis Parton). Although today it is seen as an important sentimental novel, Lillian did not share this view, writing, “A spiteful book, largely accepted as autobiographical […]. In the violet ink class.”

Also of interest in this early journal is a long passage that Lillian has copied from Carl Van Doren’s 1926 The American Novel, a critical work exploring the development of the great American novel. In the passage she has copied (in violet ink), Van Doren relates how sentimental novels ruled the antebellum literary scene. This passage begins, “But Hawthorne, and Cooke, and Winthrop were not the characteristic novelists on the Eve of the Civil War. It was the domestic sentimentalists who held the field. A brief decade endowed the nation with its most tender, most tearful classics.” Today, critics see these novels as important not only for the different literary aesthetics that they present, but also for the facets of nineteenth century life that they reveal.